The Myth of the Imminent Oil Drop

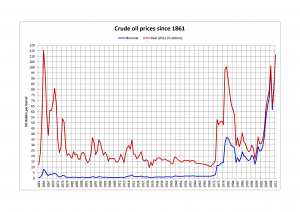

The history of oil prices is one of spikes and crashes, heated speculation and poor investment. Following this historical pattern, some are predicting another precipitous drop in the price of oil—perhaps more than $20 a barrel. However, in the past, prices were primarily based on conventional oil wells and the forces of supply and demand. The modern oil market is a bit different.

Historically, demand spikes increased competition for scarce crude, but, because of long lead-times in oil exploration and well construction, the oil industry could not simply increase supply to meet demand. This led to a spike in prices which, in turn, spurred exploration and rig building across the industry. Due to this lead-time, multiple projects—initiated during the high-price environment—tended to come online together. This resulted in large, sudden increases in supply, which subsequently brought down global prices.

Historically, demand spikes increased competition for scarce crude, but, because of long lead-times in oil exploration and well construction, the oil industry could not simply increase supply to meet demand. This led to a spike in prices which, in turn, spurred exploration and rig building across the industry. Due to this lead-time, multiple projects—initiated during the high-price environment—tended to come online together. This resulted in large, sudden increases in supply, which subsequently brought down global prices.

However, this was the world of conventional crude where, after locating a reserve, you could “strike” oil and watch as it gushed out with ease. Those days are largely behind us.

The newest additions to global supply are considered “unconventional” reserves, and are either increasingly remote (like in the Arctic or extreme deep water) or difficult to extract and refine (most notably American tight oil and Canadian oil sands). These reserves require far more capital investment and expensive, cutting-edge technology than conventional reserves of comparable size. As a result, each barrel of oil derived from these reserves is considerably more expensive. This necessitates a far higher price for them to be economical.

The key variable in the future price of oil is the marginal cost of production per barrel (often referred to as the marginal barrel). This is the cost of bringing one more barrel of oil from each well to market. This marginal cost varies considerably between producers: Iraq’s marginal cost is approximately $5 per barrel whereas oil sands production can top $122 per barrel. Overall, Bernstein Research estimates that while non-OPEC oil production is exploding, so too are its average marginal barrel costs—from about $25 per barrel in 2001 to almost $105 per barrel now.

The problem with the claims that oil will fall below $80 a barrel is that they assume the projections of global production increases without taking into account that the reserves on which those projections are dependent are only viable in a world of high prices. If the price drops below the cost of the marginal barrel of these new unconventional reserves, these fields will cease production and wait for the price to rebound; why would they spend more producing a barrel of oil than they can sell it for on the market?

The problem with the claims that oil will fall below $80 a barrel is that they assume the projections of global production increases without taking into account that the reserves on which those projections are dependent are only viable in a world of high prices. If the price drops below the cost of the marginal barrel of these new unconventional reserves, these fields will cease production and wait for the price to rebound; why would they spend more producing a barrel of oil than they can sell it for on the market?

I am not claiming that global petroleum production has peaked; indeed, there is more than enough oil on the planet to fuel us to near extinction. Rather, I believe that we have truly seen the end of $70 barrels. Barring incredible advancements in tight oil or oil sands extraction technology, ever-increasing global demand will be met by increasingly expensive unconventional reserves.

This translates to an increased impetus to begin the slow and arduous transition to renewables. As renewable technology continues to drop in price, the rising cost of oil will help close the competitive gap between them much faster. While this means trouble for the average motorist and the airline industry, it is a hopeful sign that our climate’s ultimate savior may turn out to be hard economics rather than hopeful idealism.

Rory Johnston is a Master of Global Affairs (MGA) candidate at the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs with a focus on energy markets and security.

[…] The Myth of the Imminent Oil Drop […]