Hemispheric Drug Trade Should Be a National Security Priority

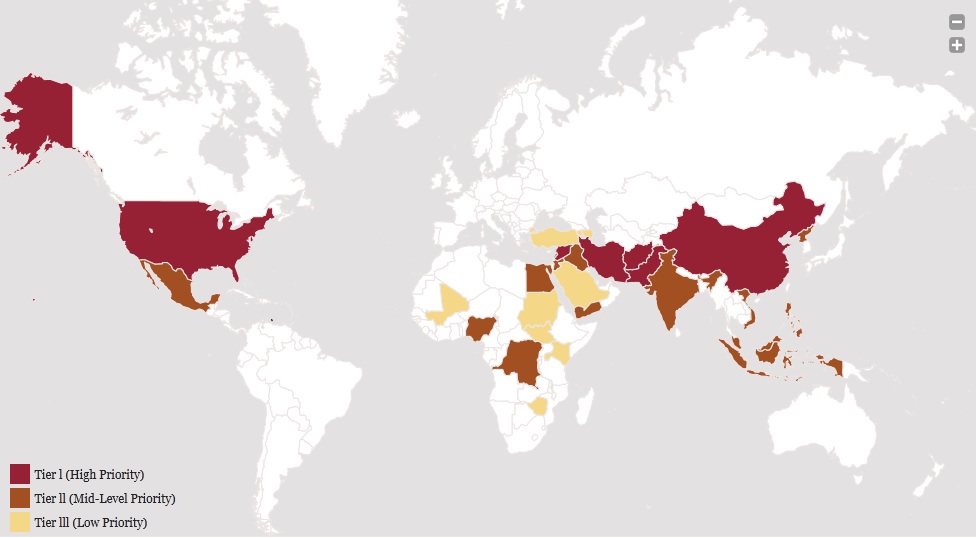

The Council on Foreign Relations’ Preventative Priorities Survey (PPS) was released yesterday, forecasting potential national security threats in 2013 based on survey data compiled from interviews of policy experts. The survey classifies nations according to a tiered-system based on the combination of (a) likelihood of threatening civil developments or state behavior and (b) their impacts on U.S. interests. Tier I security environments pose high-priority threats whereas Tier III states are classified as low-priority concerns for U.S. policymakers.

The Tier I states are a “who’s who” of daily national security headliners – China, Iran, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Syria. Somewhat surprisingly, the United States is also listed as a Tier One priority, clearly based on the potential impacts of a large-scale event (i.e. terrorist attack) rather than probability. India, Iraq, Egypt, and Indonesia are all identified as Tier II, mid-level priorities. Within the Western Hemisphere, other than the U.S., only Mexico is listed as a priority national security concern, at Tier II. No other Central or South American states even qualify as a Tier III, low priority concern according to experts polled.

Source: Council on Foreign Relations PPS 2013 –

http://www.cfr.org/conflict-prevention/preventive-priorities-survey-2013/p29673?cid=otr-partner_site-pps_2013-atlantic

In terms of what it sets out to identify – priorities within the coming year – the PPS is likely relatively accurate. Unfortunately however, this near-sightedness in foreign and defense policy also plagues top officials who are also responsible for the nation’s long-term security and relevant planning to ensure stability over time. Additionally, the PPS breaks down threats geographically by state, which fails to accurately address transnational and subnational turmoil. Approaching national security from these perspectives, it is unfathomable that the majority of nations within the Americas, specifically Latin America, would not be identified as priority concerns.

Recent trends in globalization have empowered drug trafficking organizations operating throughout Latin America. From coca production in Colombia to drug-related gang violence in Central America to political coercion over local officials in Mexico, the interconnected cycles of cultivation, transportation, sales, and the accompanying instability create a hemispheric policy problem that cannot be solved through any government’s unilateral action alone. Developments including strategic realignment by a new administration in Mexico and the continued provision of Congressional assistance through the Merida Initiative and Central American Regional Security Initiative offer hope that lawmakers are committed to this transnational policy issue.

The profitability of illicit production and trafficking is enabled, almost exclusively, by U.S. black market demand. U.S. drug demand is satisfied almost exclusively by hemispheric supply (95%-plus). The effects of legislation addressing drug legalization, migration, and trade are all relevant to the discussion on the transnational drug trade. Though spillover violence and crime into the U.S. remains unlikely, Strategic Studies Institute author Douglas Farah advises that the increasingly blended threats of terrorism, narcotrafficking, and insurgency will warrant more serious attention as an “emerging Tier I threat” if left unaddressed.

As trafficking networks of financially-driven nodes are adaptive and resilient, the U.S. needs, as a former DEA intelligence official puts it, “both a 20,000 foot strategy and a ground-level strategy,” to effectively deal with the problem holistically. This task is divided among various federal departments and agencies including Homeland Security, Justice, State, Defense, USAID, and the intelligence community. These actors are responsible for various aspects of the federal counternarcotics effort including surveillance, drug interdiction, and institution-building abroad. Though the physical safety of Americans is not typically threatened by the international drug trade, it has serious downstream consequences on health and economic productivity. Furthermore, unstable social and political conditions in Latin America severely limit opportunities for trade and investment by the United States.

There are some indications that policymakers are taking this issue seriously, such as funding increases for State and USAID diplomatic engagement in Latin America in the FY2013 budget request. Policymakers should endeavor to proactivity head off this threat rather than responding when it becomes a Tier I or Tier II priority. ASP will be publishing a detailed report on nacrotrafficking within the hemisphere after the holidays that identifies potential strategies. Tune in in January for more information.

[…] Hemispheric Drug Trade Should Be a National Security Priority […]