Let’s Hold on to Hope for Multilateral Trade Agreements

By Melinda Wood, ASP Adjunct Fellow

A surprising consensus has emerged between pro-trade Republican congressional leaders and President Trump, whose road to the White House was paved with anti-trade rhetoric. They have settled on a middle ground, where multilateral free trade agreements are rejected, but bilateral “smart trade” agreements are embraced. This new agreement on support for bilateral trade agreements allows both sides to save face and claim consistency, despite a sharp gulf between their views expressed during campaign season. Yet this emergent trade policy would come at the expense of the US’ long-term security. It’s not too late to backtrack.

For candidate Trump, the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade agreement was a “disaster” and “a rape of our country”. But for House Speaker Ryan, securing congressional passage of TPP was listed on his website as one of his top 5 priorities, until after President Trump’s Executive Order formally withdrew the US from TPP on January 23rd.

Significantly, the President has clarified that he is not, in fact, against free trade. Rather, Trump says he objected to the multilateral nature of TPP, which he believes gave up US negotiating leverage. From now on, Trump says the US will only participate in bilateral trade negotiations with allies such as the UK and Japan, where he believes the US can reach better deals.

Without missing a beat, pro-trade Republicans have lined up behind the President. In an awkward mincing of words, Ryan praised Trump for “follow[ing] through on his promise to insist on better trade agreements.” Accepting that TPP is over, congressional leaders are now grasping at new opportunities to secure bilateral FTAs. During his visit to London last week, Ryan called for a US-UK trade agreement as soon as possible, sounding almost as if he was back to his old talking points:

“We are more determined than ever to lead. We don’t want China to write the rules of the 21st century global economy. We want to do that. We want a level playing field for our businesses. And yes, we want free trade deals, but they have to be smart trade deals.”

Yet it is hard to see how a US-UK bilateral will beat China to the task of writing the rules of the 21st century global economy. In the vacuum left from TPP, China is leading the way in negotiations which are nearing conclusion for the Region Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a multilateral trade agreement between 16 countries in the Asia-Pacific region.

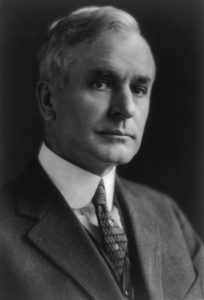

Secretary of State Cordell Hull

Ryan’s words belie the fact that a rejection of multilateral trade is a seismic shift in US security policy which has been in place since the end of WWII. Believing that a lack of economic integration between nations in the 1930s was a significant contributor to the war, the Roosevelt Administration promoted trade liberalization as a means of securing long-lasting peace. Roosevelt’s Secretary of State Cordell Hull firmly believed that bilateral trade agreements amounted to “preferential” deals that only hardened alliances against each other. The US was the key actor in convening the allied victors to establish the Bretton Woods multilateral financial architecture in order to better integrate national economies. US foreign policy has continued to emphasize stability through international economic interdependence in the decades since, from opening to China, to détente with the Soviet Union, where trade was used as a tool to reduce the threat of nuclear war.

While bilateral agreements promote economic integration between two specific countries, they come with broader costs. They emphasize dramatic power imbalances and result in preferential and vastly differing standards of agreements, as countries pick winners when deciding who to negotiate with, and under what terms. A small country like New Zealand cannot demand standards for labor, environment and human rights when negotiating with much larger neighbors in Asia, but it achieved these commitments through TPP.

With a greater number of participants in multilateral agreements, individual sensitivities can be offset against broader gains, and the risk of not being part of a trade zone including a country’s neighbors can provide significant leverage to influence the domestic policies of other nations. We saw many examples of this in TPP, from domestic reform of Japan’s highly protected agricultural sector, to forcing Malaysia to amend its law to improve the treatment of human trafficking victims. Perhaps the most significant commitments were from Vietnam, which agreed to enforceable labor standards for the first time in history. In addition to agreeing to new freedoms of association, collective bargaining and minimum work conditions, including abolition of child labor, Vietnam signed a TPP implementation plan directly with the US that provided even greater certainty that it would carry out specific actions. Without the benefits of TPP, these concessions will not be realized.

At the American Security Project, we have previously argued that TPP would have built peace through increased prosperity, free exchange, and support for strategic and military alliances. We have also argued that the US must trade with China’s neighbors to secure their support for US foreign policy. TPP at its core was intended to support the US strategic pivot to Asia. Upon release of the final TPP text in 2015, Paul Ryan recognized this, stating that a successful TPP would mean greater US influence around the world. Bilateral agreements are poor substitutes, and would likely exclude non-traditional allies such as Vietnam, Malaysia and the Philippines, which are heavily influenced by China.

Although the President has acted definitively with respect to TPP, there is still hope that he may come to see the benefits of multilateral agreements for securing US interests abroad. He has repeatedly demonstrated a willingness to walk back positions that he has previously allowed himself no wriggle-room on. In less than 100 days in office, he has reversed completely on his support for NATO (“I said it was obsolete. It’s no longer obsolete”), on labelling China a currency manipulator, and on intervening in Syria. It is not inconceivable that he might take a second look at TPP for allies such as Japan, and he has remained notably silent on the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership with the EU, which Ryan plugged during his visit to London. There is still hope for US participation in multilateral rule-setting for trade.