Courtesy of Beraldo Leal on Flickr

Courtesy of Beraldo Leal on Flickr

A Response to S. 1221: “Countering Russian Influence in Europe and Eurasia Act of 2017”

The Senate has passed legislation with bi-partisan support that would reinforce Obama-era sanctions and impose new sanctions on Russia. Russia’s continued military actions in Ukraine and Georgia, and its efforts in the cyber realm to sow disinformation and undermine trust in European and Eurasian election processes provided the impetus for these sanctions. In addition to the arms, oil, and financial sanctions on Russia that were introduced during the Obama administration, this legislation proposes allocating funds to countries that are most susceptible to Russia’s cyber influence. In theory, these funds would be channeled through both federal agencies like the State Department and various intergovernmental organizations like NATO and OECD to help vulnerable nations improve their resiliency against Russian cyber campaigns.

Though this bill is not yet law, it still represents a clear articulation for a possible strategic route in achieving concessions from Russia on the aforementioned issues. For this reason, it is imperative to recognize and consider the empirical issues that will determine whether these sanctions will prove effective against Russia. Though this may seem intuitive, it is worth keeping in mind that the imposition of sanctions is not alone a sufficient condition for gaining policy concessions. Rather, it is crucial to consider whether the sanctions target appropriate assets for achieving the stated policy goals and enforcement mechanisms, as both have significant implications for their success.

Considering this new legislation, there are now two primary goals that Russian sanctions are trying to achieve: the removal of Russian forces from the Crimea and Eastern Ukraine, and to mitigate Russian efforts to spread propaganda and disinformation over the Internet. As to the first goal—which was first addressed by the Obama-era sanctions—it is rather plain to see that these are not creating prohibitive conditions for Russia’s continued presence in the region. This is not to say that sanctions have had zero impact on Russia, as blocking the export of oil technology as contributed to its economic downturn starting in 2013. Yet the fact that this legislation does nothing to ramp up the severity or scope of the Obama-era sanctions is a strategic shortcoming.

The new measures this bill proposes are not really sanctions but requests for funding to vulnerable states to defend the integrity of their networks against Russian cyber-attacks. At this point it is hard to say whether these funds will prove effective in blocking Russian probes, but it is worth mentioning that deciding to only defend against Russian cyber-attacks will not reduce Russia’s latitude to act and it will continue to build its cyber capabilities.

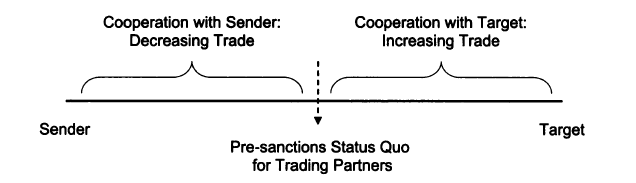

When looking at how sanctions against Russia have been enforced, Elena McLean and Taehee Whang provide a useful framework. By constructing a continuum that looks at how third party states act toward targets of sanctions.

From: Elena V. McLean, and Taehee Whang, “Friends or Foes? Major Trading Partners and the Success of Economic Sanctions,” International Studies Quarterly 54, no. 2 (June 2010): 430.

They find that sanctions tend to be more successful in achieving policy concessions from the targeted state when additional states cooperative in upholding sanctions. On the other hand, when other states maintain economic ties with the sanction target, they are more likely to fail. Empirically, sanctions against Russia fall on the latter half of this continuum as Russia has maintained a significant trade relationship with the outside world. Furthermore, there is clear indication from Germany—one of Russia’s largest trading partners—that willingness to suffer the economic consequences from blocking interaction with Russia via sanctions is fading.

From this, there are clear reasons to seriously doubt the efficacy of the Russian sanctions passed in the Senate in achieving their intended goal. The purpose here is not to pose what we should do in lieu of sanctions, as different sanctions that do a better job at undermining Russia’s staying power in Ukraine without significant side effects could be the best strategic route. Rather, this analysis should serve primarily as a cautionary tale that de facto strategic initiatives meant to address foreign challenges should not be continued simply for a “sticking to our guns” mentality. Instead good policy implementation requires consistent reexamination to make sure ends and means are in sync.

I agree with you 100%. A very concise assessment of the situation.