We Left a Void in Cuba. Now, Our Adversaries Are Filling It

By Gabrielle Jorgensen, Director of Public Policy, Engage Cuba

Thursday, April 19 marked a historic transition of power in Cuba. Rather than seizing the moment as an opportunity to rebuild relations, the U.S. seemed further from Cuba than it had been in decades. Just days before, Vice President Mike Pence had publicly snubbed Cuban Foreign Minister Bruno Rodriguez at the Summit of the Americas before publishing an op-ed with a similar tone. And when asked his opinion on the day of the transition, the President, perplexingly, responded with, “We love Cuba. We’re going to take care of Cuba.”

Mr. President, we are not taking care of Cuba. Depriving Cuba’s nascent private sector of its primary customers by tightening U.S. regulations on travel is not “taking care of Cuba.” Sending Cubans off on a costly journey to Georgetown, Guyana to get their visas is not “taking care of Cuba.”

Russia’s Victor Leonov leaving Havana Harbor

But U.S. adversaries are, and they show no signs of relenting. Russia has extended a debt forgiveness policy of 90 percent to the Cuban government, alleviating them of nearly $30 billion in Cold War-era debt. Russian state firms have invested billions in 55 new infrastructure projects in Cuba, including a massive railway modernization project. In 2017, in light of Venezuela’s declining oil production, Russian state energy company Rosneft resumed oil shipments to Cuba for the first time since the 1990s. Putin has also expressed interest in modernizing Cuba’s military equipment and has more than once docked a colossal intelligence vessel named Viktor Leonov in Havana’s harbor.

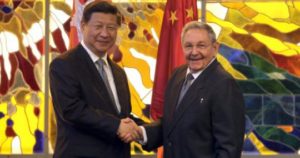

China, too, has gotten cozier with Cuba. Following its quietly potent strategy of economic statecraft in Latin America, China has pledged to finance a new container terminal in Santiago and offered new credit options, including zero-interest financing, to the Cuban government. Chinese companies have announced plans to build at least 25 biomass plants and two solar power generators on the island, while Huawei, a Chinese tech giant, has an agreement with Cuban state internet provider ETECSA to install broadband internet in Havana. Already, Huawei powers hundreds of Cuba’s wi-fi hotspots.

China, too, has gotten cozier with Cuba. Following its quietly potent strategy of economic statecraft in Latin America, China has pledged to finance a new container terminal in Santiago and offered new credit options, including zero-interest financing, to the Cuban government. Chinese companies have announced plans to build at least 25 biomass plants and two solar power generators on the island, while Huawei, a Chinese tech giant, has an agreement with Cuban state internet provider ETECSA to install broadband internet in Havana. Already, Huawei powers hundreds of Cuba’s wi-fi hotspots.

These developments in our hemisphere are problematic for national security, as illustrated repeatedly by experts, including 16 retired military flag officers, former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, and Senator Patrick Leahy. The final law enforcement pact between Cuba and the Obama Administration increased cooperation on counterterrorism, cybersecurity, migration, narcotics interdiction, smuggling, human trafficking, and money laundering. Joint initiatives by the U.S. Coast Guard and Cuban authorities have proven fruitful, particularly in preventing drug trafficking, which the Trump Administration has claimed is a policy priority. But without continued U.S. engagement in the post-Castro era, we can easily imagine these agreements faltering. In the absence of adequate U.S. diplomatic staff on the island—which is at its lowest point since the 1970s—the U.S. has fewer avenues to advance our interests. As Moscow and Beijing continue to bolster their security collaboration with Havana, the new government could begin to favor new partners over the U.S.

Without eyes and ears on the ground in Havana, the State Department is limiting its own capacity for strategic policymaking. With Cuba forced into the dark under the embargo, the U.S. cannot advance its human rights agenda on the island. We cannot afford to give up our seat at the table while our adversaries increase their economic influence in Cuba. Instead, the U.S. should fully staff its embassy in Havana, promote economic engagement, and facilitate U.S. travel to Cuba, all of which help to bring stability and prosperity to a country 90 miles off our shores.

President Miguel Diaz-Canel is a seasoned bureaucrat, but he is not a Castro. He will face a real challenge in protecting the principles of Castro’s revolution while navigating monetary reforms that are critical to saving an ailing economy. His government will continue to seek foreign investment in almost every sector. Russia and China are not yet the political influencers they could be, but that day may well be on the horizon. The U.S. must get back in the game while a transitional Cuba and its new president are forced to decide their future.

Read the full Engage Cuba report, The Dangers of U.S. Withdrawal from a Post-Castro Cuba on U.S. adversaries’ actions in Cuba here.