The October Revolution: 100 Years Later

By Ricky Gandhi

This month marks the 100-year anniversary of the October Revolution, an event that ultimately transformed the Russian system and identity. 100 years later, Putin has forged a new identity — one that mixes elements of the Soviet Union with more western ones.

The System Yesterday

Russian identity has been historically difficult to define due to different tsars, changing geography, and various ethnic groups. Realizing the potential conflicts this could cause, later tsars engaged in nationalistic polices knows as Russification. This attempted to unify the region by establishing a common language and culture. In short, Russification served to strengthen tsarist rule.

Of course, this did not last. However, the Bolsheviks did not ignore the benefits of cohesion. At first, Lenin and his party promoted unity through diversity. He figured the best way to promote Soviet ideology was to respect local customs and present it in native languages. This policy, known as korenizatsiia, or “indigenization,” served to create a common socialist identity.

Stalin took a different route. He believed empowering local communities could threaten centralized rule. Therefore, instead of respecting locals, he forced them to adapt the Russian language and culture.

Stalin also ramped up oppression of all forms and promoted glorification of the Soviet system. As a result, the elements of society that traditionally helped define Russian heritage became heavily suppressed. The peasant communities, the Orthodox church, and the arts all suffered.

After Stalin’s death, Khrushchev scaled back on the oppression, a period known as the Khrushchev Thaw. However, this led to revolts such as the Hungarian Revolution in 1956. The brutal Soviet reaction illustrated that while some forms of dissent were tolerated, major demonstrations aiming to change the system were absolutely forbidden.

Seeing the issues freedom can cause, Brezhnev ramped up censorship and increased military spending. The latter helped enforce the Brezhnev Doctrine. It stated that each Communist party bears responsibility in protecting others, even with force. This gave Russia a free pass to embark on military campaigns in its near abroad to preserve centralized rule.

Gorbachev later shattered the centralized order through perestroika and glasnost. Again, allowing political dissent and more individual freedoms paved way for mass demonstrations that ultimately destroyed the USSR.

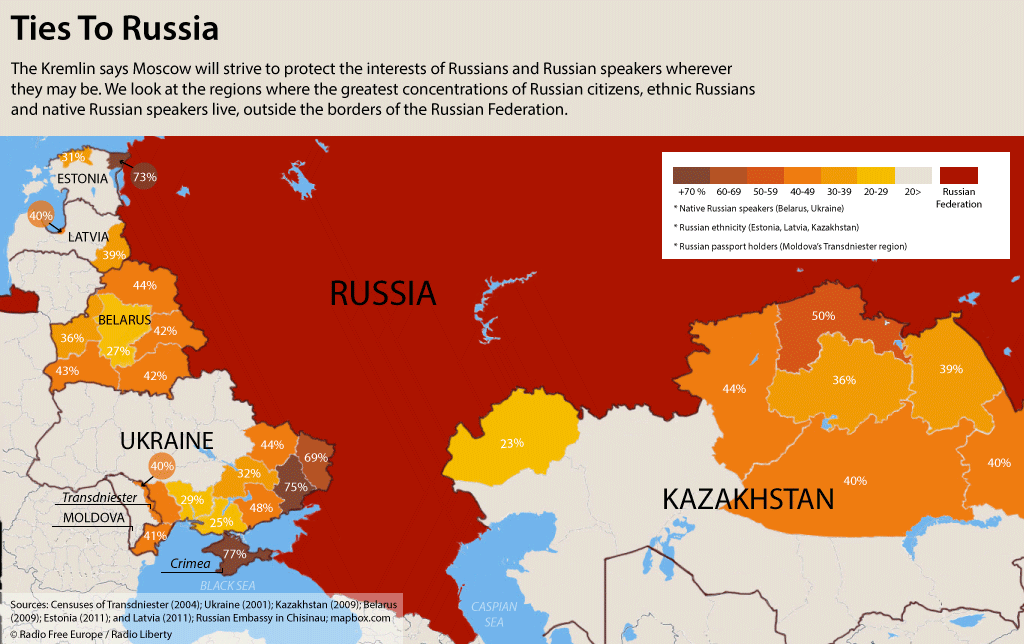

After disintegration, tens of millions of Russians living in Soviet states suddenly became foreigners in a former homeland — “a major geopolitical disaster,” according to Putin. The remnants of the Russian Empire now had to redefine themselves once again, but this time with much of its population living in the “near abroad.”

The System Today

After the tumultuous Yeltsin years, the population yearned for legitimate authority, a relatively freer society, and unity. To do this, Putin developed a hybrid system of past Sovietization polices and (limited) Western liberalism. This had the effect of appealing to nostalgia while also paving a new path forward. The goals again remained the same: stability and strong centralized rule.

Part of the nostalgia involved restoring Russia’s status as a world power. This is why major military reform and efforts to join liberal organizations, such as the World Trade Organization, became major policy objectives. Both would improve Russia’s global standing while making the population feel once again proud of their homeland.

Additionally, Putin revived some Soviet symbols and restored the old Soviet anthem with updated lyrics. These actions reinvigorated a form of Russian identity at a time when the country faced a bleak future.

His foreign policy also induces nostalgia. Russians, for example, overwhelmingly approved the annexation of Crimea — a region they believe is historically theirs. The Kremlin has also shown a desire to protect ethnic Russians in the near abroad. This allusion to the Brezhnev Doctrine obviously concerns the Baltics, as “protecting Russians” can be a false justification for sending in the Russian military

Source: Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty

Putin also introduced some liberalization. The Orthodox Church and religion, for example, once again play prominent roles in society. The President also appealed to religious and ethnic minorities in order to foster inclusiveness.

Individuals could also speak freely about the politics without repercussion. Liberal dissent in media and online, while becoming increasingly censored, still exists (e.g. Novaya Gazeta). However, all of this comes with a major caveat: people cannot organize freely against the government. In addition, dissenters who can amass a huge following and threaten centralized rule will likely face repercussions.

The Kremlin remains heavily paranoid toward popular uprisings. They oppressed major opposition figures and denounced “color revolutions” abroad. They have even shown reluctance in commemorating the October revolution, instead focusing on the violence and instability it caused. Moscow would much rather promote the notion of a strong and unified Russia.

The System Tomorrow

100 years following the October Revolution, Putin has created a hybrid system that tries to maintain a strong national identity, albeit at the expense of political and social liberties. Ventures abroad have also resulted in international condemnation.

Still, Putin remains undeterred. He has incredibly high approval ratings, the military continues to modernize, and the economy is growing again. As such, this system will likely serve as a model for future governance, especially considering the youth (18-24) support Putin more than any other age bracket at 86%.

This means Russia will continue an active foreign policy, promote a multipolar world, give lip service to tackling corruption, and slowly diversify the economy. Liberalization has backtracked, and will only improve incrementally (if at all) so that it doesn’t threaten power.

In other words, the future of Russian politics is unlikely to change much. Hoping for pro-Western reforms at this time is pointless. The population widely supports a hybrid Russia, even at the expense of liberty. Russia does not want to be Western—it wants to be Russian.