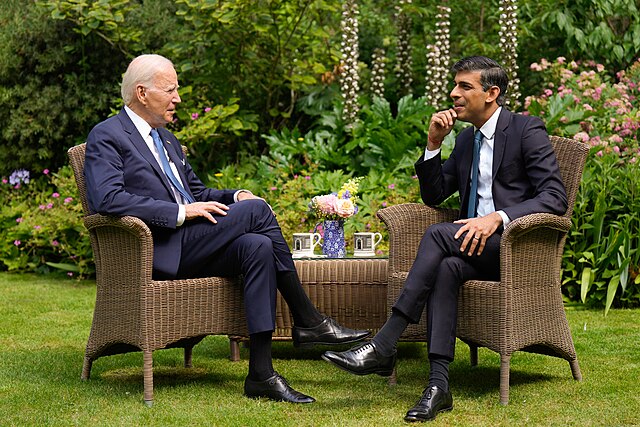

President Joe Biden and Prime Minister Rishi Sunak met in July. Image: The White House

President Joe Biden and Prime Minister Rishi Sunak met in July. Image: The White House

Trans-Atlantic Export Controls: Leaping Promises, Lagging Oversight

On Wednesday, three out of four agencies in the United Kingdom’s Committees on Arms Export Controls called to disband and reform the parliamentary authority responsible for overseeing national export control mechanisms. Highlighting inadequate member participation, lack of transparency from the executive branch, and system-wide undermining of its work, the Committee’s complaints highlight a growing disconnect across both the United Kingdom and the United States: as executive branches move full steam ahead with new investment and trade restrictions against China, the agencies that implement and enforce them are struggling to keep up.

Over the past four years, trans-Atlantic export controls have expanded due to escalating tensions between the American and Chinese governments. China’s wealth and influence have grown significantly over the past two decades, along with its ambitions to expand its regional authority and maintain authoritarian control over its populace. While these ends run counter to the ethics of the liberal democratic order, its means pose a more direct threat: China exploits global markets to absorb foreign technology and incorporate it into its defense and intelligence capacity, and if it can’t purchase the technology it needs, it isn’t afraid to steal it. The result has been nearly $320 billion in annual losses to the U.S. economy, with similar ramifications reported by the United Kingdom.

In June 2023, the Atlantic Declaration, signed by U.S. President Biden and U.K. Prime Minister Sunak, promised that new “technology protection toolkits” would curb China’s ability to obtain and leverage emerging technologies. The tools in question comprised sanctions, export controls, and investment restrictions, which the United States and the United Kingdom had been implementing since 2022. Following the Declaration, the U.K. Department for Business and Trade stopped approving license applications for nearly all semiconductor exports to China. Simultaneously, the Netherlands and Japan signed similar deals, multiplying the overall impact of trade restrictions on China.

While these actions are encouraging, export oversight and enforcement mechanisms have struggled to keep up. In the United States, the number of items under restrictions quickly surpassed the capacity of systems and staff. As a result, the agencies responsible for export and investment restrictions in the United States were expanded dramatically. The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) now operates under a budget of $41 million in 2024, up from $15 million in 2020, and the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) maintains a budget of $139 million, up from $72 million. The capacity of these agencies has been bolstered through stronger and more frequent fines, the most notable being the BIS’ $300 million penalty levied against Huawei. Still, experts say that many Chinese companies are evading these mechanisms by smuggling components across borders or creating shell companies licensed in different regions.

The situation bodes worse for the United Kingdom, which lacks the ability to double or triple its expenditures on economic control enforcement. The Department for Business and Trade plans to spend £157 million on export controls, sanctions, and free trade agreements in 2024, a decline of nearly 7% from fiscal year 2023. Meanwhile, the investigation load on the Export Control Joint Unit is the highest it has ever been, with rejected export licenses climbing from 40 in the first quarter of 2020 to a record-breaking 186 in the first quarter of 2023. Last week, the Unit admitted to missing its processing time targets due to the “added complexity” of new restrictions.

The race to fulfill the promises of Biden and Sunak has come at the expense of cutting oversight and accountability mechanisms, of which the proposed disbanding of the Committees on Arms Export Controls is just one example. In November, Parliament loosened export restrictions in key areas, increasing the government’s agency in deciding which purchases meet the threshold of a national security risk. Yesterday’s Joint Special Report highlighted that the U.K. Government committed to reviewing and justifying the expansion of trade controls by fall 2023 but has not done so. In December, the United States exempted its ally from licensing and reporting requirements under the Armed Exports Control Act. Some U.S. legislators aim to go further by exempting allied states from the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR), which would save British companies more than $500 million in yearly licensing and reporting fees.

These moves share a common purpose: to compensate for Chinese trade losses by granting greater autonomy and flexibility to executive powers. Putting the excitement of a new global technology race aside, the U.S. and its partners must seriously consider the long-term effects of streamlining their defense against China. It might be easy for the U.S. to bloat the trade and investment authorities of itself and its partners while the threat of China looms, but the backlog is ramping up—both in spending and autonomy.