Photo courtesy of Tariquehasan17 on Wikimedia Commons

Photo courtesy of Tariquehasan17 on Wikimedia Commons

Climate Change-Induced Heatwaves May Make South Asia Unlivable by 2100

Record-breaking temperatures have blazed through Europe this past week, leaving seven dead and millions seeking relief in an area ill-prepared for such heat. Scientists calculated that climate change made the heatwaves five times likelier. Such temperature extremes have become predictable occurrences in other parts of the globe.

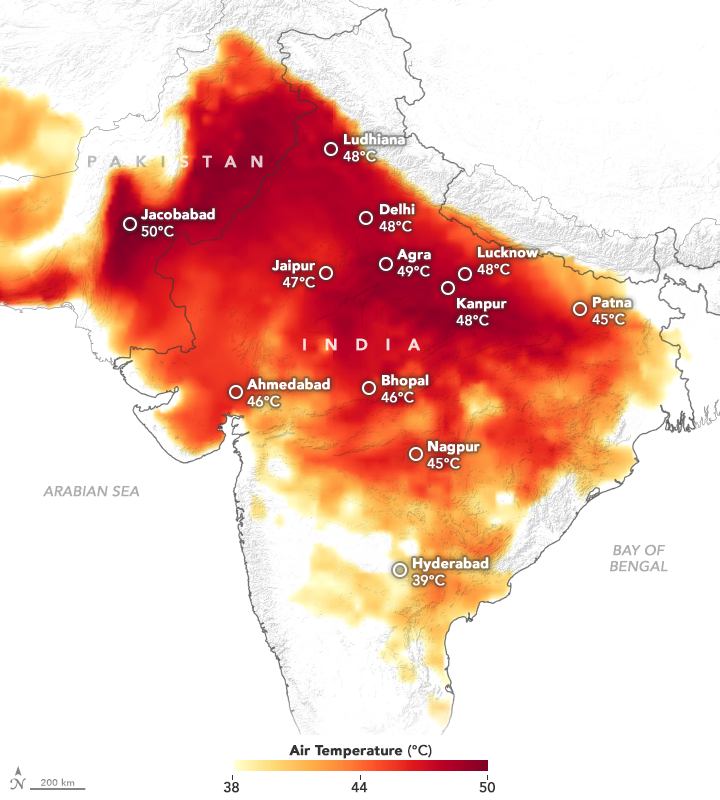

In India, high temperatures are becoming a normal, if hazardous, part of life. The most recent heatwave, starting in May and continuing until the onset of the monsoon this week, claimed at least 130 lives. Climate research predicts that deadly heatwaves will become the norm in South Asia, pushing the upper limits of human survivability.

Climate Exposure in South Asia

India, Bangladesh, and southern Pakistan are home to 1.5 billion people and are among the poorest countries in the region. Much of the population is dependent on subsistence agriculture that requires long hours working in the sun.

This makes them particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change.

The most recent heat wave hit temperatures as high as 123 degrees, following a pattern of increasingly intense heatwaves. The number of Indian states hit by heatwaves has grown from 9 in 2015 to 23 this year. Since 2010, more than 6000 people in India have died because of heatwaves. These numbers could increase significantly as temperatures quite literally become too hot to bear.

Hot weather’s deadly effects come from the combination of high temperature and high humidity, which is measured by an index called wet-bulb temperature. As humidity increases, less moisture evaporates, and the human body becomes less capable of maintaining its internal temperature. Past the wet-bulb temperature of 95 degrees Fahrenheit, the human body cannot cool itself for longer than a few hours.

Currently, about 2 percent of the Indian population is occasionally exposed to extreme wet-bulb temperatures (between 89 and 94 degrees). According to a 2017 study, by 2100 that number could increase to 70 percent. About 2 percent of the Indian population could be exposed to the survivability limit of 95 degrees.

Security Risks

The affected areas of South Asia are concentrated around densely populated agricultural regions. Some are major urban areas with populations over 2 million people where having air conditioning is a luxury. Extreme heat, outdoors agricultural work, and no AC mean that heatwaves pose fatal risks to people in these areas.

Deadly heat stresses hospitals and other medical systems, as well as disaster management systems. In the northeastern state of Bihar, hospitals were inundated with people suffering from heatstroke; 49 people died in just 24 hours.

Historic droughts have decimated water resources, leaving many village wells dry. More than 6,000 tankers supplied water to villages in the central state of Maharashtra amid conflict between neighboring states. In Madhya Pradesh, fighting broke out over water resources. Police were deployed to protect water trucks and wells.

The heatwaves also triggered mass migration, and tens of thousands of villagers fled their homes. In some areas, up to 90% of the population left, leaving the sick and elderly to fend for themselves. This may place stress on neighboring states or countries also facing heat emergencies or who are unwilling or unable to accept refugees.

Going Forward

As climate change makes heatwaves more common, country officials will have to tackle both the causes and consequences of rising temperatures.

Officials in India have a few individual recommendations for dealing with extreme heat: avoid the sun, avoid chilled drinks than can shock the system, cover your head and ears, hydrate, and seek medical attention at the earliest sign of dehydration. These actions alone are not enough in the face of climate change.

One city in India, Ahmedabad, created a “Heat Action Plan” that includes mandatory midday breaks for workers, an early warning system for “red alert” days, public tree-filled parks and gardens, and cooling wards in hospitals. These policies are largely credited for saving hundreds of lives during a heatwave in the city in 2015. While this type of comprehensive approach to heat safety is a step in the right direction, most cities in South Asia do not have such plans.

There is still time to avert the most severe effects of climate change. Action must be taken to tackle the region’s major pollution and carbon emissions problems. Without large-scale action on carbon emissions, the coming changes could make South Asia unlivable for its 1.5 billion residents, sparking global consequences.