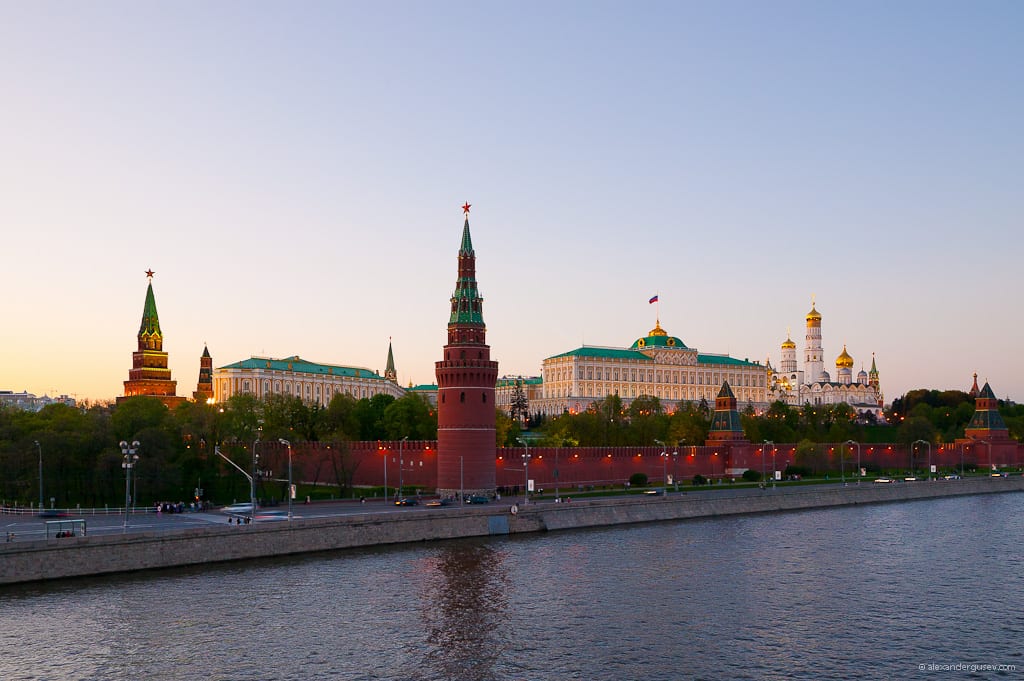

Courtesy: Alexander Gusev

Courtesy: Alexander Gusev

Hints of Democracy in Russia’s Governance

After three terms of Putinism, and the beginning of a fourth, it becomes easy to repeat the simplified discussions we hear in the news regarding Russia’s system of governance. A conversation about Russian governance usually involves the terms authoritarianism, autocracy, and of course, dictatorship. Despite the echoes of Cold War nostalgia that runs across the headlines, some experts contend that Russia is a hybrid regime; a mix of authoritarianism and managed democracy. As Russia’s economic situation stagnates, its system leans more so to the authoritarianism side of the spectrum. Because of this fluctuating mix, some prefer to deem Russia an ‘overmanaged democracy.’

‘Overmanaged democracy’ implies centralized power in the executive branch, formal institutions of democracy, and the “systematic gutting of these institutions” through substitutions which remain dependent on the central government. Regardless, there are certain democratic elements within Russia’s system that incorrectly deem Russia an outright authoritarian state. These elements are the following:

1. Russian elections

There’s a belief that Russian democracy is solely limited to voting. Sources confirmed this year’s presidential election held a record low level of voter fraud. Through the years, it is clear that President Vladimir Putin is capable of winning a ‘fair’ election, as there is simply no viable opposition. That is not to say that Russian elections are actually fair. Yes, it is widely known state media coverage favors Putin and that the Kremlin manipulates political parties that participate in the election. However, that does not mean there is no truth to President Putin’s ratings and that he does not enjoy widespread support.

2. “Ratingocracy?”

It is well known; Russian leaders pay extreme attention to public support. One can argue that this obsession goes so far that they are willing to make concessions to win back public support. For example, earlier this year, President Putin’s ratings dropped to 54%. The drop marked the first time Putin’s ratings since 2014 that his ratings dropped below 60%. Analysts theorize the drop in ratings was correlated to pension reform. After the drop, President Putin went on live television and proposed changes to the pension reform. Overall, does the “ratingocracy” allow a certain amount of accountability from Russian leaders? Yes, even if the amount of accountability is to be debated.

3. Russian ideas about democracy

Perhaps, the most striking feature about Russia’s system is how its citizens feel about it. The Russian Federation is an enormous multinational country with a unique historical background with a diverse set of opinions regarding what it means to be democratic. It would be wrong to assume that debate and public discussion in European nations is the same within Russia. The following was palpable in multiple surveys conducted by the Levada center from 2014 to 2016. In 2014, 62% of Russians surveyed asserted that Russia needed a democracy. However, they also responded that Russia needed a democracy that corresponded with its national character and asserted Western style democracy was destructive to the nation. In 2015, most Russians expressed the belief that democracy is a social construct and that order is more important than democracy. In 2016, Russians continued to support the idea that Russia needs a special kind of democracy with its unique characteristics. Five months after this poll, Russians also deemed the stabilization of Russia’s political and economic situation more important than democracy and freedom of speech. Too often, Western analysts interpret, or attempt to interpret this data as a sign that the Russian government succeeds at brainwashing its own people. Nonetheless, it is impossible to discern the precise effects of Russian national character, the influence of the Russian media, and the historical consciousness acquired from the turbulent nineties. Overall, the data shows Russians possess different definitions of democracy and different priorities in the domestic arena than their western counterparts.

In conclusion, these characteristics in the Russian system make it difficult to assess Russia’s democratic elements through a western lens. Analysts must understand the complexities of Russia’s system of governance and must not overlook the nuanced ways in which public will and sentiment affects the Russian decision-making process. Overall, understanding Russia’s system is crucial to building sustainable and credible U.S. foreign policy towards Russia.