China’s One Belt, One Road: An Ambitious Strategy Challenging the U.S.

In a major international summit in Beijing, featuring over 30 heads of state, the Chinese government announced pledges of over $100 billion in Chinese investment to support their new “One Belt, One Road” (OBOR) program. Some analysts anticipate that this investment could increase to over $1.4 trillion in Chinese funds. This ambitious investment would bolster China’s economic and geopolitical strategy to link together continental Asia and Europe.

In a major international summit in Beijing, featuring over 30 heads of state, the Chinese government announced pledges of over $100 billion in Chinese investment to support their new “One Belt, One Road” (OBOR) program. Some analysts anticipate that this investment could increase to over $1.4 trillion in Chinese funds. This ambitious investment would bolster China’s economic and geopolitical strategy to link together continental Asia and Europe.

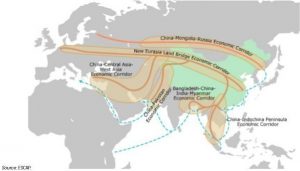

China’s ambition in its OBOR strategy is clear. China is making a bet that the future lies in re-joining Eurasia as a single economic entity. By making infrastructure investments in a “New Silk Road through Central Asia” and a “Maritime Silk Road” through the Indian Ocean, China is attempting to knit Europe and Asia together along both maritime and overland trade corridors that had long been neglected. This is consciously harkening back to the ancient and medieval trade routes of the past, even including pictures of camel caravans in its official documents.

One of the Chinese Government’s official OBOR cartoons

The One Belt, One Road initiative appears to be a combination of geopolitical, economic, and military strategy put forward by Chinese President Xi Jinping to achieve multiple Chinese aims. Xi’s speech at the Belt and Road Forum offers clear historical analogies hearken back to a time when China saw itself as the “Middle Kingdom” – literally at the center of the world. The economic implications are clear: China seeks to continue to export. Not only will China export the consumer goods we know well in the United States, but the country needs to export its unfinished goods to maintain domestic employment. One example will show: China has a surplus capacity of steel production, with its smelters expected to produce over 100 million metric tons of steel this year than they can consume. For the last several years, that surplus has been dumped onto world markets, driving down global steel prices and drawing threats of a tariff war between China and other steel producers, including the United States. Instead of reducing steel production (which would cost jobs and harm politically important steel manufacturers), the OBOR initiative would export that steel as a part of its aid to support local infrastructure.

OBOR will help China’s national security because the government believes it faces an internal threat from the Muslim-majority Xinjiang region. By linking Xinjiang to eastern China, it will both encourage economic growth and migration of ethnic Han Chinese to the region. This is the same calculus the Chinese have used to pacify Tibet. Connecting the former Soviet Central Asian countries to China will also create a stable source of resources like natural gas and minerals. The geopolitical calculus is similar: by tying countries in the region to Chinese finance, Chinese business, and Chinese goods, the country will create a centripetal force that draws nations to the center: the Chinese “Middle Kingdom.” This effort to lead is buttressed through soft power pledges to address global challenges like climate change, biodiversity, corruption, gender equality, and the rights of the disabled.

If this vision sounds familiar to Americans, there is a reason. This was how the United States tied the western alliance together throughout the Cold War: the Marshall Plan and the force of American business and finance created a virtuous cycle that helped both the United States and its allies to prosper. More recently, the United States had put forward a vision for the future that competed with China’s trans-continental OBOR: that the 21st Century would be anchored around the Pacific Rim, as embodied in the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP). Unfortunately, the United States formally pulled out of the TPP in President Trump’s first week in office. Without a competing alternative, the United States is only left to protest when allies join new Chinese institutions like the Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank (AIIB) or the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).

The mark of a global superpower is the ability to shape geopolitics through long-term strategies lasting decades. If it is sustained, the One Belt, One Road strategy shows that China is moving from being a power reacting to events, to one that is trying to shape the global system. The United States used to have such a global strategy – leading through free trade, human rights, and military strength – but has lacked any consistent message over the last two decades. In the early days of the Trump Administration, such consistency is even further from the forefront. To remain a superpower, the United States cannot simply rely on military power: America must consistently lead as it has done in the past. Perhaps China’s challenge will finally catalyze Washington to remember that?

I posted onto my LinkedIn platform – on 19 August 2012, ‘It is amazing to consider the opportunities to create wealth and jobs as transportation infrastructure (road, rail and air) is being developed between Paris and Beijing. The best way to explain it to Americans who may not have been fortunate enough to travel along the New Silk Road is by using the example of America’s interstate highway system – courtesy of the Smithsonian Institute exhibit in Washington, DC’

Sadly, American firms have not taken up the challenge to get involved… I certainly want to appeal to US cities, which have sister cities in any of the dozen or more countries involved in infrastructure development, especially supply chain logistics to seek for ways to establish entrepreneurial activities in collaboration with those cities.