A Grand Strategy for the Climate

On September 29, moderator Chris Wallace made history by asking the first climate question at a U.S. presidential debate in twenty years. Left off Wallace’s original list of debate topics, the climate crisis made the cut only after an environmental pressure campaign. The failure of climate change to make the shortlist is glaring for any number of reasons: the record-breaking series of fires sweeping America’s Western states; an unprecedented hurricane season for the vulnerable Gulf Coast; and the Arctic’s rapid shift to a new climate. Perhaps most glaring, however, is that two-thirds of Americans agree the government needs to do more on climate change.

Climate has been invisible not only on the debate stage but within U.S. grand strategy as well. There is a growing consensus that climate security is national security, but this view has not yet reached the architects of American foreign policy. It is time for that to change. For if grand strategy is “a nation-state’s theory about how to produce security for itself,” as Barry Posen writes, cutting emissions is the only way to produce long-term U.S. security. No other strategic decisions will matter in a world on fire.

CONVERGING THREATS AND U.S. NATIONAL SECURITY

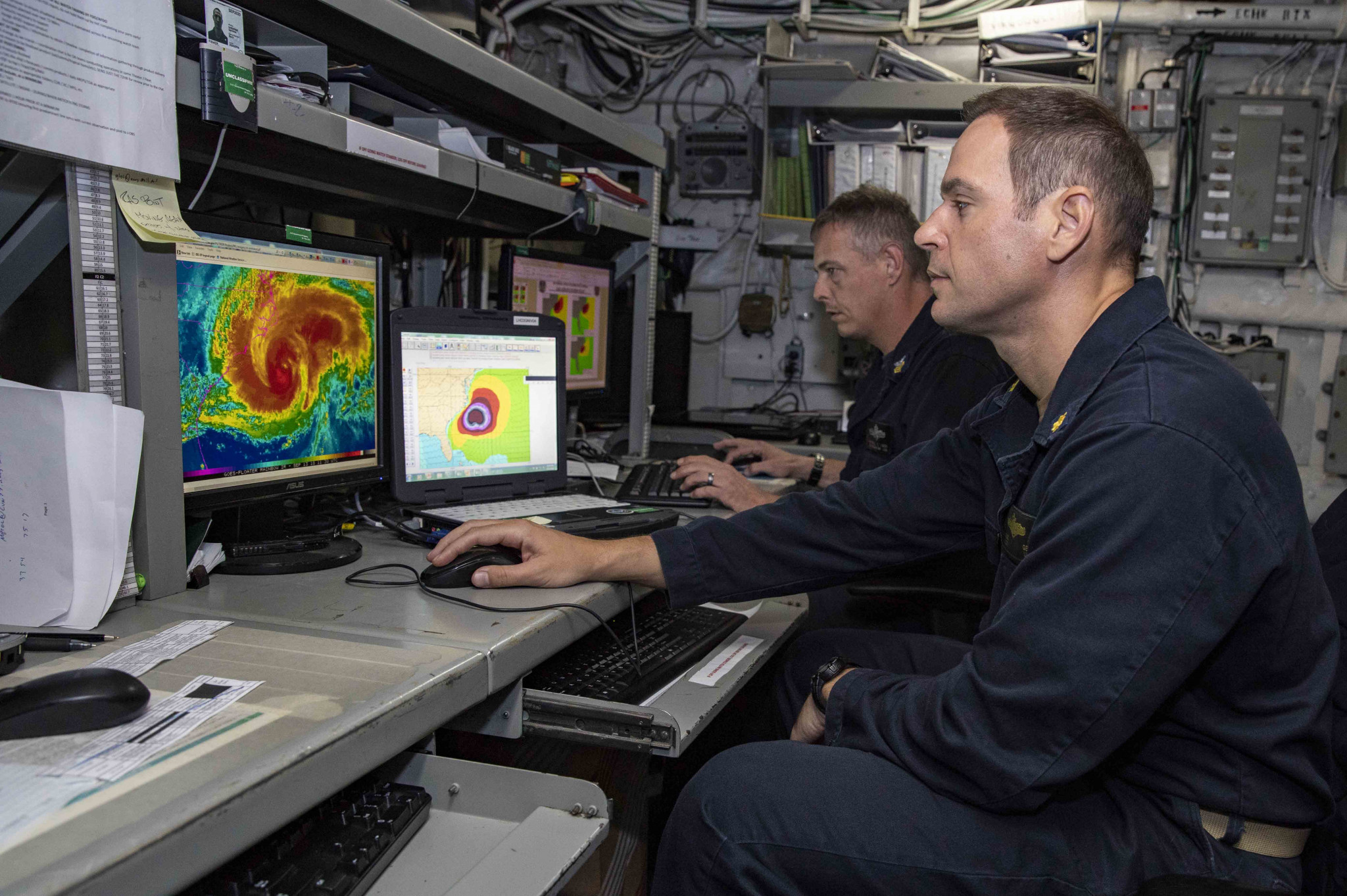

Climate change is such a potent threat because the dynamics of a warming world favor multiple, simultaneous crises. Overlapping disasters trigger cascade effects that overwhelm U.S. response capabilities both at home and abroad. Domestically, the recent convergence of natural disasters has put great stress on emergency management systems only designed to handle one problem at a time. Overseas, the compounding effects of poverty, climate change, and armed conflict sow instability and threaten to pull the U.S. military into more frequent humanitarian missions. The problem of climate migration also looms large, since climate change will make certain parts of the world uninhabitable.

The Department of Defense (DoD) has long recognized the role of climate change as a threat multiplier. Since 2010, the Pentagon has acknowledged the need for a strategic approach to the effects of climate change on DoD operating environments, missions, and facilities. Commanders across all six geographic combatant commands have described the dangers of climate change for their respective areas of responsibility. In August 2020, the U.S. Army reiterated just how seriously the military takes climate change by releasing its Army Climate Resilience Handbook. Since debates over America’s grand strategy often hinge on the question of U.S. military power, it is long past time grand strategists take climate change as seriously as does the DoD.

CLIMATE POLITICS AS GEOPOLITICS

America’s grand strategists must also recognize the pivotal role climate policy plays vis-à-vis their favorite preoccupation: the rise of China. Chinese leadership is eager to leverage the lack of U.S. climate leadership for geopolitical gain. This is evident from President Xi Jinping’s recent pledge before the United Nations General Assembly that China will be carbon neutral by 2060. As the economics of energy rapidly shift—and as Big Oil looks unlikely to ever fully recover from the effects of COVID-19—states will reap increasing rewards for investments in renewable technologies. In other words, to the electrostate will go the spoils.

The question is whether we can take Xi’s pledge at face value. Although China dominates the clean energy market, it is still the world’s largest consumer of coal. To keep up with rising demand, China has nearly tripled its energy output since 2000—largely by relying on fossil fuels. Xi’s carbon-neutral target date of 2060 should give us pause as well since scientists agree the world must reach zero-carbon emissions by 2050 to prevent climate catastrophe.

A WAY FORWARD

Luckily, unlike great power competition, the decarbonization contest is not zero-sum. Although U.S. policymakers should be concerned with the strategic implications of leaving China’s superiority in clean energy unchecked, there are also promising avenues for Sino-American climate cooperation. In fact, given the tense state of relations between the two countries, climate change is likely one of the only viable cooperative options left.

As the two largest emitters of greenhouse gases, the U.S. and China should both be at the forefront of global decarbonization efforts. By actively engaging on climate issues, U.S. policymakers can help hold China accountable for meeting its needed emissions targets. America cannot simply rejoin the Paris Agreement and expect a return to normalcy, however: other countries are likely to be skeptical that deed will follow word. The U.S. will have to prove its commitment through bold domestic climate action that goes above and beyond its 2015 Paris pledge of 26%-28% below 2005 levels by 2025. First, however, policymakers need to decide the climate matters.

This article was originally published by the Albritton Center for Grand Strategy at the Bush School of Government and Public Service.