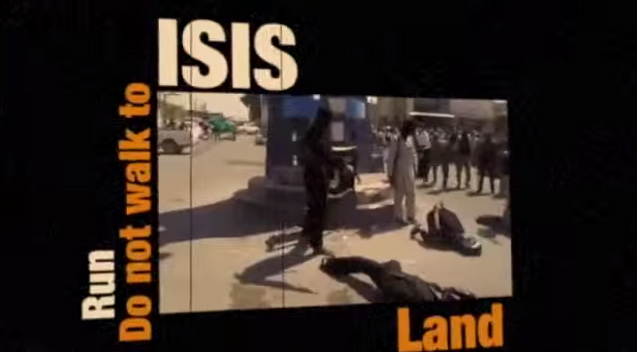

A screenshot from a recent State Department video

A screenshot from a recent State Department video

The New Digital Divide and Countering Extremist Propaganda

A great deal of attention is being given recently to the State Department’s efforts to combat extremism online. Notably, a video recently released by the State Department’s “Think Again Turn Away” campaign contains graphic video of some of the many atrocities committed by ISIS in the name of creating a caliphate.

The editing quality of the video itself appears amateurish in nature, featuring repeated stock effects reminiscent of a first time video editor who’s just discovered the effects panel in iMovie. Though making the video look amateur may have been intentional, some have criticized it in comparison to the high quality material that terrorist organizations are producing.

Despite this, the video has seen nearly 800,000 total views on YouTube since its original posting in July. For a State Department production, this number is impressive, but it doesn’t tell the whole story. A significant portion, if not a majority of these these views could have come from the United States, as views shot up drastically immediately after coverage by BuzzFeed and 24-hour cable news.

This raises the question, “Who is the target audience?” According to Time, Ambassador Alberto Fernandez, who leads the Center for Strategic Counterterrorism Communications (CSCC), explains it’s not the extremists themselves, but rather, “the people the extremists are talking to, trying to influence. It’s people who have not yet become terrorists.” This makes sense, but of course, that pool is wide enough to encompass American citizens as well as foreign audiences.

Challenging extremist propaganda online is no simple task. Unlike a radio or TV station, which have often been destroyed or jammed in time of war, countering propaganda on the internet is a much trickier enterprise. By nature, internet propaganda is diffuse, easily replicable, and incredibly difficult to eliminate. It does not need to come from a central source, but instead may become dependent on its audience to produce. In essence, it is self-perpetuating. Extremists have access to the same online tools as the Department of State, placing them on an even playing field.

It is thus extremely unlikely that a single video, campaign, or message issued by the State Department can disarm the extremist messages on the internet. Problematically, government messages tend to hold little sway online in comparison to celebrities and a particular user’s friends, who dominate much of the “social” aspect of social media. While being a government lends a certain amount of credibility, it also tends to be a handicap online as it is drowned out by the cacophony of other voices which may appear more credible or more worthy of attention to individual users.

Even though there is a science to the elements that make a video go viral, inclusion of these elements is not a guarantee of success. It often takes many attempts to make material go viral. Up until this point, the Think Again Turn Away campaign has received relatively little attention—but the overtly graphic nature of this new video is in itself a primary reason for it having gained so much attention.

But in terms of gauging the success of programs like Think Again Turn Away, we may have to think differently about what constitutes effectiveness.

We must understand that when it comes to extremist recruitment, we are not talking about combating a government which can be defeated, but rather a system of individualized decision making. Extremist propaganda is often a blanket technique, under which individuals make personal decisions on whether to join a terrorist cause. It is thus difficult to establish metrics on an individual level to see who has been convinced to not join ISIS.

So what constitutes effectiveness with this type of campaign?

Effectiveness should be gauged in the actions of other internet users to carry anti-extremist messages. Likes and retweets are only one small component. Is the audience using the rhetoric provided by the State Department? Is it developing its own anti-extremist messaging? Is it doing anything at all to counter extremist messaging? After viewing this material, or any other online campaign, what does the target audience actually do? This is the new digital divide—measuring the gap between apathy and action.

The State Department’s efforts are necessary, but it has limited resources and limited reach to effectively blanket its entire intended audience. If an effective network to combat extremism online is to be tapped, it must be the network that is most credible to those most likely to join extremist causes. Ultimately, that doesn’t mean a government, it means average people.

[…] The New Digital Divide and Countering Extremist Propaganda Matthew Wallin […]

[…] The New Digital Divide and Countering Extremist Propaganda Matthew Wallin […]

[…] information. While the Center for Strategic Counter Terrorism Communications is potent, much more needs to be done by the United States […]

[…] to answer why the U.S. often has difficulty dissuading individuals from turning to terror, Sonenshine […]