The difficult art of stabilization in Somalia

The port city of Kismayo in the south of Somalia is the focus of considerable effort to build a political path to long term peace in today’s Somalia. Since the Islamist insurgency, Al Shabaab, was pushed out of the city by a combined force of African Union soldiers from Kenya and Somali militias at the end of September, Somali leaders and international partners have been scrambling to build on the fragile sense of peace in this clan-divided city.

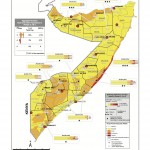

Over a year since Somalia’s famine hit the headlines in the United States more than two million of the country’s estimated population of ten million remain remain dependent on food aid. Last month, the United Nations and Oxfam forecast a deteriorating humanitarian situation, worse in the southern regions near Kismayo. Tens of thousands reportedly fled in the lead up to the operation to remove Al Shabaab from the city. A population desperately worried about food and security makes for a difficult environment in which to generate stability.

A series of bombings in the city since September this week resulted in large-scale arrests by the Kenyan forces eager to maintain security. Underlying complex clan tensions and rival interests vying for control of the port’s revenue exacerbate the precarious security situation. Long term peace will depend on how different clan groupings see their prospects for political power and economic wealth around the port’s economy play out.

Stabilization, in recent years, has been the seemingly impossible art of trying to build a sense of confidence among people recovering from conflict through a range of security measures, early impact development projects and support to nascent government institutions. However, for an international force seeking to manage tensions in a newly liberated yet impoverished community it can often boil down to making the right call on a few pivotal issues; and just as much about what isn’t done as what is done.

In today’s Kismayo there is one significant hurdle to building a sense of peace. When Al Shabaab had control of this sizeable port it was extracting an estimated $25 million a year in funding for its  activities from the export of charcoal, particularly to countries in the Gulf. In response, earlier this year the United Nations Security Council imposed a ban on the import of charcoal from Somalia though enough countries kept on trading for Al Shabaab to make money from the trade, and the local economy flourished.

activities from the export of charcoal, particularly to countries in the Gulf. In response, earlier this year the United Nations Security Council imposed a ban on the import of charcoal from Somalia though enough countries kept on trading for Al Shabaab to make money from the trade, and the local economy flourished.

Following the quick exit of Al Shabaab from Somalia’s second largest city, international actors are left with a difficult problem. Media who have visited the seaside city recently, and know Somalia well, have reported on growing dissatisfaction among the Kismayo population as the ban is enforced, the charcoal trade stops and, most importantly, sources of income dry up.

Thinly stretched around the country, with minimal force protection, the African Union troops are closest to the Somali people and have an interest in helping them rebuild their lives. Representatives from the countries that provide troops to the African force in Somalia have petitioned the United Nations for the ban to be lifted, at least temporarily. Nevertheless, the new Somali President concerned about proving his authority to international partners and keen to manage the power that flows from this lucrative trade, has publicly reinforced the continuing ban on the charcoal trade.

Charcoal production and trade is a significant part of the Somali economy though it is linked to deforestation, the degradation of fragile pasturing land and soil erosion. It is likely that some of the growing charcoal stockpile in the city continues to be traded illegally. Even with Al Shabaab apparently out of the city, the problem is that a lifting of the ban would still benefit the Islamist insurgency, as they retain links into the city’s economy and have control where the charcoal is harvested outside the urban center.

Charcoal production and trade is a significant part of the Somali economy though it is linked to deforestation, the degradation of fragile pasturing land and soil erosion. It is likely that some of the growing charcoal stockpile in the city continues to be traded illegally. Even with Al Shabaab apparently out of the city, the problem is that a lifting of the ban would still benefit the Islamist insurgency, as they retain links into the city’s economy and have control where the charcoal is harvested outside the urban center.

The United States and its international partners see blocking the flow international finance for terrorist organizations as an important measure in the fight against Al Qaeda and its allies, such as Al Shabaab. For communities trying to maintain a livelihood and put food on table amidst conflict it can mean the difference between life and death.

Where conflict and regular famine has been a way of life for decades, the intervention by the African Union force risks further upsetting what is already a complex web of relationships. Understanding the powerful interplay between vested interests and economic incentives is essential to steering a community towards long term stability.

When the United Nations Security Council discusses a resolution on Somalia next week what it decides will have a direct impact on the lives of people in Kismayo, whatever it does. The United States and its partners have an important role in understanding what is happening to Somalis, impartially arbitrating disputes and keeping the people on side.