UNESCO

UNESCO

Obama at Hiroshima: A Fitting Capstone

The Obama Administration has toed a fine line with remarkable consistency when it comes to nuclear weapons and arms control

And so, in the end, Mohammed will go to the mountain. President Obama has become the first sitting president to visit Hiroshima, an appropriately matching bookend to a presidency seemingly up-and-down with regard to nuclear weapons and arms control. From the lofty peaks of his Prague speech and Nobel Peace Prize to the victory of New START to the current contentious debate over modernizing existing US nuclear forces, the Obama Administration has shown great nuance, even if to some observers it seems more like a schizophrenia. But in truth, the administration has been remarkably consistent in its approach to nuclear arms, and its track record reflects both idealism and pragmatism – the latter in too great proportion for dedicated arms controllers; the former too overly pronounced for unreformed Cold Warriors. The president might lay out a new policy in his remarks – or he may quietly acknowledge what was once done to the city – but in the years between Prague and Hiroshima, he has laid the foundation both for a continued US nuclear deterrent and for its eventual abolition.

The Pledge

President Obama launched his approach to arms control, nuclear weapons, and disarmament with the Prague speech in April 2009. While themes of European solidarity and the continuing relevance of NATO loomed large, Obama also used the speech to announce “America’s commitment to seek the peace and security of a world without nuclear weapons.” It is upon this phrase that the American arms control debate has turned. Obama went on to caveat that goal: “I’m not naive. This goal will not be reached quickly—perhaps not in my lifetime. It will take patience and persistence. But now we, too, must ignore the voices who tell us that the world cannot change. We have to insist, ‘yes, we can.’” And in the concrete steps the United States would take, Obama threaded a fine line between the dream of a nuclear-free world and the reality of the long, arduous path such a world would require. The United States would “reduce the role of nuclear weapons in our national security strategy, and urge others to do the same.” But, critically, he declared unequivocally that “As long as these weapons exist, the United States will maintain a safe, secure and effective arsenal to deter any adversary, and guarantee that defense to our allies” [emphasis mine]. Global Zero, in other words, could and can only be achieved on a universal basis, and not unilaterally.

The United States would seek a new arms control treaty with Russia – that much could be pursued on a bilateral basis – but the rest was multilateral: try to ratify the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, look to finalize a Fissile Material Cutoff Treaty, strengthen the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, establish a new framework for nuclear energy, develop international enforcement mechanisms for treaty violators, and work with the international community to pressure North Korea into abandoning its nuclear weapons program. That multilateral focus would, in turn, set the course of administration nuclear policy over the next seven years.

Fulfilling the Promise

The policy-focused Prague speech was followed by the Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) in 2010. The NPR report echoed Prague but focused more on the practical implications of further arms reductions, with sections on “reducing the role of U.S. nuclear weapons,” “maintaining strategic deterrence and stability at reduced levels,” and “sustaining a safe, secure, and effective nuclear arsenal.” The document specifically acknowledged in its last chapter, addressing the desire for a world free of nuclear weapons, that “this goal will be a long-term effort, not the work of one Administration.” Essentially, the NPR sought to enshrine a reduced role with far lower numerical requirements for nuclear weapons in US strategic thought, laying the foundation for disarmament on a multilateral basis at some point in the future.

President Obama and Russian President Medvedev sign New START in Prague, 8 April 2010 (photo: the Kremlin)

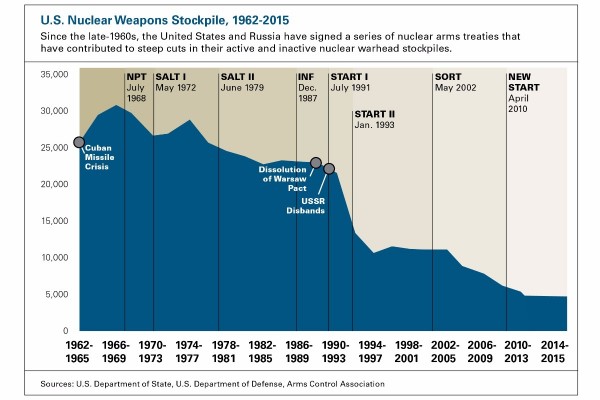

The administration implemented the NPR’s findings over the next four years with a string of successes at international diplomacy. The New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), signed to coincide with the release of the NPR in April 2010, reduced the number of deployed nuclear weapons to 1,550 for both the United States and Russia by 2018, and preserved the inspection regime of the original START. Many who had advocated a new arms control treaty were dismayed that the treaty continued to count delivery vehicles and not warheads, and that it merely limited the number of deployed weapons rather than requiring the actual destruction of any. Hawks decried the treaty as a “giveaway” to Russia, as the number of Russian strategic nuclear weapons would likely have fallen to that level anyways, and furthermore, the treaty did nothing to constrain Russian “tactical” nuclear weapons. New START managed to contain the parameters of future Russian and US nuclear development while simultaneously keeping a robust, hedged nuclear force.

As New START entered into force and inspections continued, the Obama administration found little appetite among other nuclear powers – particularly China – for a mutual arms control framework. Despite this failure, the United States, along with the other P5, Germany, and the European Union, successfully crafted and signed the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) with Iran in 2015. The agreement limits the latter’s enrichment capabilities and existing stockpiles, and subjects most of Iran’s nuclear program to inspection, monitoring, and verification. Thus the administration was able to curtail, at least a little while longer, the spread of nuclear weapons globally; the scenario in which an Iranian bomb would lead to widespread proliferation in the Middle East will thankfully be unrealized.

Stalling Out

The quest for a multilateral arms control treaty remains unfulfilled, and the largest barrier to reducing weapons among the established nuclear powers (with the possible exception of the United Kingdom, which seems increasingly prepared to jettison its nuclear deterrent force) seems to be an stalemate between Russia, China, and the United States. China won’t reduce its own arsenal until Russian and US levels have shrunk. Russia has no interest in further bilateral treaties and desires a multilateral regime, but is even more focused on US missile defense and precision munitions. India will not engage in arms control without Chinese participation, and China refuses under the NPT to acknowledge India’s possession of nuclear weapons. And so on it goes. Meanwhile, dedicated arms controllers in the United States have argued for unilateral US arms reductions as an alternative to the costly modernization program underway, or at least the cancellation of an entire class of delivery vehicle (typically the nuclear variant of the Long-Range Standoff Missile). But unilateral reductions have been given a cold reception.

This, of course, is not unusual. It reflects a continuous strain of US strategic thinking, rather than a new level of stubbornness. Bernard Brodie, in his foundational Strategy in the Missile Age, tried to strike a similar balance: “One must first ask what degree of arms control is a reasonable or sensible objective. It seems by now abundantly clear that total nuclear disarmament is not a reasonable objective. Violation would be too easy for the Communists, and the risks to the non-violator would be enormous. But it should also be obvious that the kind of bitter, relentless race in nuclear weapons and missiles that has been going on since the end of World War II has its own intrinsic dangers” (Princeton University Press, 1967, p. 300). Brodie was writing in 1959, long before the first arms control or confidence-building measures had been established, but in a simpler environment where the arms race was bilateral. Given the overlapping, multilateral nature of the current strategic picture, similar prudence is in order. That multilateral requirement also explains why progress towards a world without nuclear weapons seems to have slowed as of late.

The Legacy

President Obama has played a part in reducing great power nuclear arsenals, as well as preventing needless proliferation throughout the world (should there be a failure in this regard, it would be North Korea’s continuing nuclear weapons development and provocations). He has, at the same time, reaffirmed his pledge that “as long as these weapons exist, the United States will maintain a safe, secure and effective arsenal.” Aging, deteriorating weapons meet none of these criteria, and so the president has positioned the US strategic deterrent for a significant upgrade through a “bow wave of modernization.” That modernization is all the more significant as US delivery vehicles – and accompanying strategic planning – have remained fundamentally unchanged since the 1980s. It is, paradoxically, that upgrading of the arsenal (without increasing it) that will serve to reinforce US deterrence and ensure its effectiveness at even smaller numbers in the future, just as befits a world moving towards global zero.

The president has not been receptive to the idea of unilateral reductions, but there are other measures the United States could take without requiring a partner nation. The tremendous backlog of nuclear warheads awaiting dismantlement at Pantex and other storage facilities could be addressed by investing in additional physical capabilities, and by prioritizing dismantlement over refurbishment. This would have the added effect of reducing the number of nuclear objects potentially susceptible to theft, an unequivocal benefit. Further dismantlement might potentially reduce the size of the hedge force, satisfying those who claim the United States’ treaty-based reductions have been broad but shallow.

And so Obama arrives at Hiroshima having kept his pledge. He will speak, as he often does, by acknowledging the grim realities of today while looking forward to a brighter tomorrow; a world in which some nuclear weapons are necessary while working towards one in which they are utterly obsolete. Hiroshima is the ideal setting in which to proclaim the United States’ lasting, vested interest in ensuring that it and Nagasaki forever remain the sole targets of nuclear strikes. But to do that, the United States will require international partners. One president and one country can only do so much achieve a vision of a nuclear-free world; a post-Obama arms control regime will have to balance the strategic aims and neuroses of the panopoly of nuclear powers. Having done his best to walk a very fine line, however, he can hand over the US nuclear arsenal to his successor, having brought the United States two terms closer to “never again” – both in word and in deed.